From Siam to the Swedish Museum of Natural History

In the early 20th century, a handful of people, including the Swedish count Nils Gyldenstolpe, a researcher and Lund University alumni, found themselves caught up in a convoluted narrative. This story revolved around importing Siamese deer and bison horns, and teakwood boxes filled with bird skin, previously belonging to Mr. Emil Eisenhofer, a German engineer working on the Northern Railway of Siam. Gyldenstolpe purchased these horns and bird skins in 1917 on behalf of the Royal Swedish Natural History Museum’s vertebrate division, where he worked.

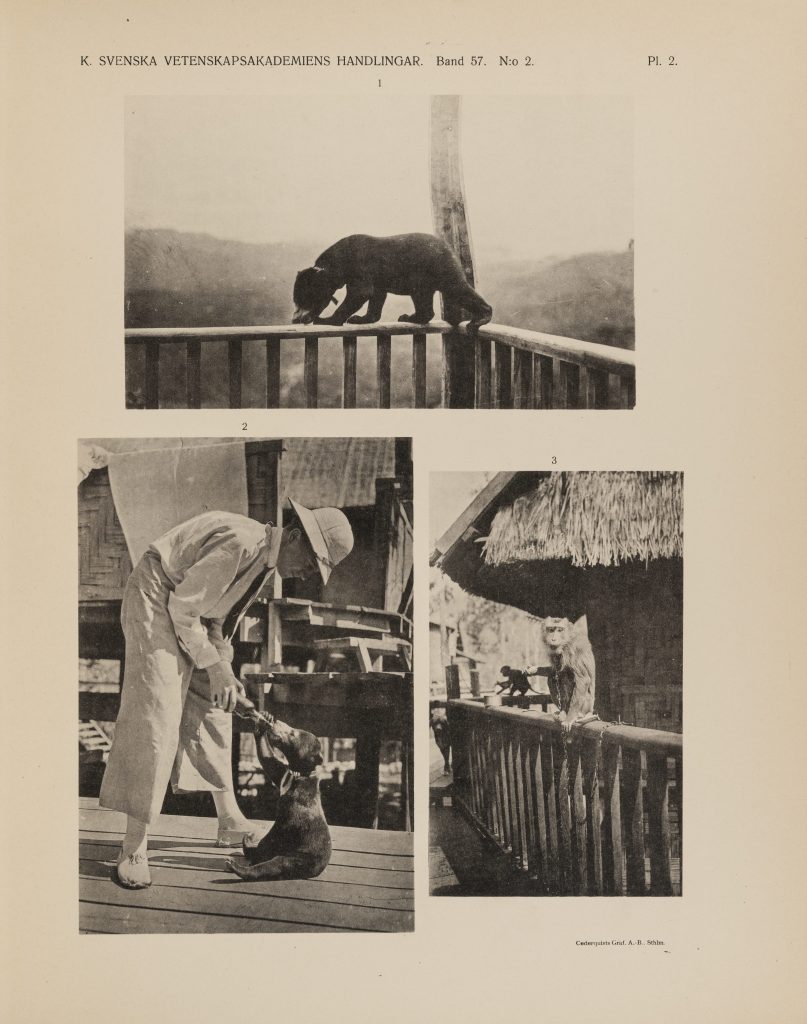

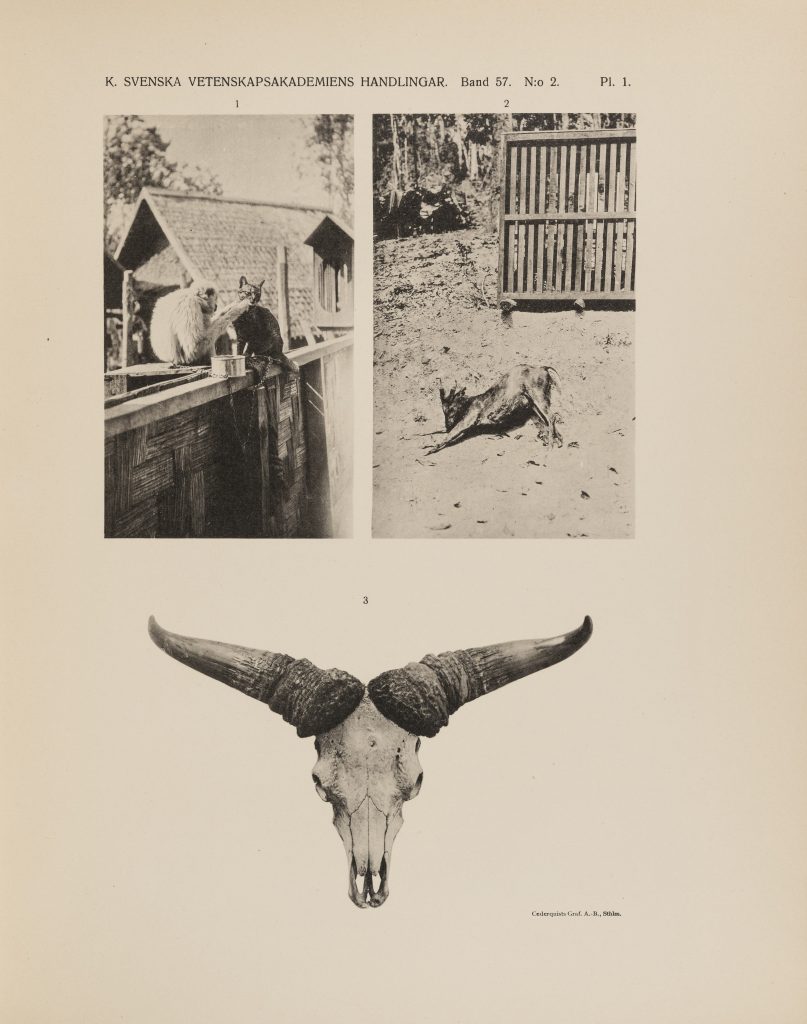

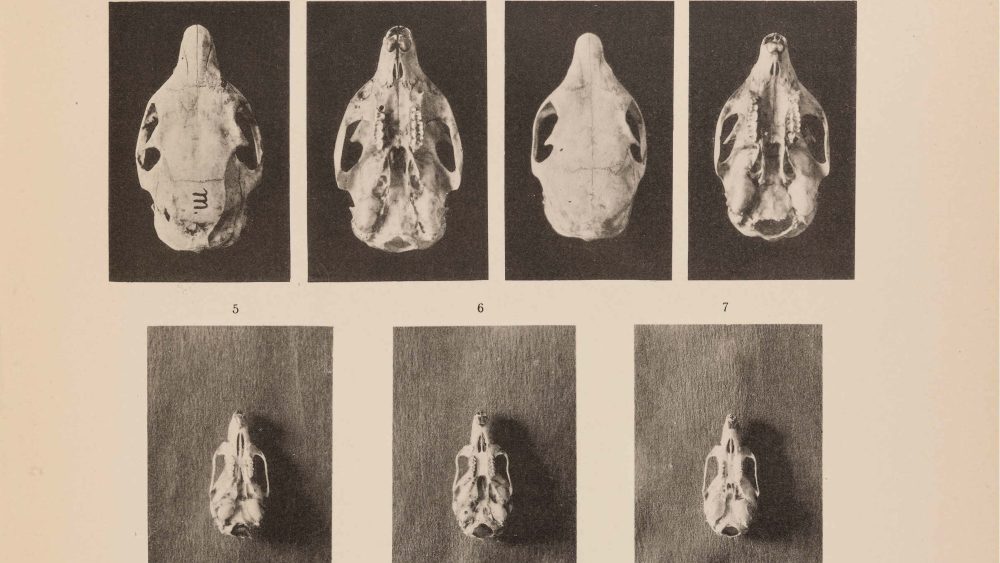

Before our narrative from the archives unfolded, Count Gyldenstolpe had traveled to Siam in 1911–1912 and to Siam and the Siamese Laos State 1914–1915 to hunt and collect specimens of mammals. The results were later published in a zoological report by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1916. During his travels, he most likely encountered Eisenhofer, who had accumulated a collection of bird and mammal specimens while working on the railroad line to Chiang Mai from Bangkok. What further proves this connection is that Gyldenstolpe authored an article in The Journal of the Natural History Society of Siam (vol.1, no.3, 1915) about Eisenhofer’s bird collection.

When Gyldenstolpe later sought to buy Eisenhofer’s zoological items, the sale established a paper trail through a collection of letters from October 1917 to March 1920. Through this correspondence, insight is gained into the complex shipping operations, ownership conflicts, and expenditures that occurred throughout this affair.

Eisenhofer tells “The Custodian of Enemy Property” that he has sold the collection

Our story begins with a letter from Eisenhofer, written to the Custodian of Enemy Property on 6 October 1917. This agency handled property claims resulting from wartime actions, represented in the correspondence mainly by H.H. Prince Bidyalankarana but also Prince Bydialongkorn. Together with other Germans, Eisenhofer was incarcerated when Siam joined the Entente in WWI and declared war on Germany and Austro-Hungary in July 1917. Eisenhofer’s collection was subsequently seized by the Custodian of Enemy Property. The letter, understood as a notification rather than an inquiry, implies that Eisenhofer thought he had maintained some influence over his collection since the wording of his letters indicates he had facilitated a sale.

“I have the honour to forward to you attached a copy of my letter to the Custodian of Enemy property regarding deer and bison horns, belonging to the Swedish Museum at Stockholm. The skins belonging to these horns are (…) also the property of the said Museum (…). Further I beg to point out, that I collected since many years large varieties of birdskins, which I have placed at the Disposal of Count Nils Gyldenstolpe of the same Museum.” (6 October 1917, Sgd. E.E. to The Custodian of Enemey Property H.H. Prince Bydialongkorn)

The Swedish embassy questions; is the sale valid?

Regardless of the tone of Eisenhofer’s letters, the sale would not be as straightforward as it might first appear. In the correspondence written from his imprisonment, Eisenhofer suggests that the collection be transferred to the Swedish Consulate. He next expected them to take possession of the cases on behalf of Count Gyldenstolpe and the Swedish Royal Museum of Natural History. However, when the Danish chargé d’affaires C. von Holck (also de Holck in the letters), representing the Consulate, learns about Eisenhofers’ transaction, then apprehensions arise. Von Holck questions whether the dealing was done correctly, resulting in him sending a handful of letters to both Eisenhofer and the Custodian of Enemy Property. He asks the Custodian if they knew the collection was Gyldenstolpe’s, which they express uncertainty about. In an extract from a letter received 22 October 1917, referring to an earlier letter from the Custodian of Enemy Property, von Holck cites the custodian as stating;

“'(…) I am afraid I cannot decide the ownership of the above-mentioned articles on the mere assertion of Mr. Eisenhofer but am prepared to consider any evidence that you may advance in proof of the Count’s title to the articles claimed.’

Referring to the above I beg to ask you to produce at your earliest convenience the evidence asked for in his Highnesses letter.” (22 October 1917, C. Von Holck, Chargé D’Affaires to Mr. E. Eisenhofer, Internment Camp, Bangkok.)

As a result, von Holck began pressing Eisenhofer for proof of the sale. It is now uncovered that Eisenhofer had been in the process of selling the zoological objects but that the transaction was indeed not finalized before the war broke out.

Who has a rightful claim?

As the unsettled arrangement is revealed, the Custodian of Enemy Property offers to sell the birdskins to Count Nils Gyldenstolpe through the Swedish embassy under the same original terms asked by Eisenhofer. As the zoological objects’ ownership is further questioned, it also becomes unclear if Eisenhofer regarded the collection as Gyldenstolpes or if he merely wanted the count to have priority of purchase. In some letters, it seems that the collection was considered a gift from Mr. Eisenhofer to Count Gyldenstolpe, and in some, it appears like the affair was less bound to happen. This becomes especially clear when reading the following excerpt of a letter written by Gyldenstolpe, dated 14 November 1918;

“(…) a copy of a letter from Mr.Eisenhofer to me was also forwarded to you, and in this letter Mr.Eisenhofer said ‘that I gladly present you the birdskins’. In a later letter, however, Mr. E[isenhofer]. has written to the Royal Swedish Consulate General that he had only given me ‘the right or priority to purchase the birdskins’. He therefore seems to have changed his mind during the meantime (…)” (14 November 1918; Nils Gyldenstolpe, Royal Natural History Museum to Mr. C. de Holck, in charge of the Royal Swedish Consulate General, Bangkok)

This letter also reveals that Eisenhofer had not set a price but had informed the Museum staff that they would be allowed to inspect the items before an agreement was settled.

Who sets the price?

As previously indicated, the custodian of enemy property had agreed to sell on the same conditions as Mr. Eisenhofer. As a result, the Museum naturally requested to inspect the objects before paying. However, due to the raging World War, transportation to Sweden was deemed unfeasible. Modern readers may perceive a decrease in urgency in communication until we reach the collection of letters delivered after the war ended in late 1918. The Museum once more requested that the objects be inspected before payment could be settled, to which the Custodian answered in a letter on 25 August, 1919 that they would not be able to comply with such a request.

“(…) with reference to Count Gyldenstolpe’s proposal that the birdskins be forwarded to him in Sweden for inspection before a price is offered for them by the Museum, I regret that in view of the distance and the difficulty of shipping, I do not see my way to comply with the count’s request.” (25 August 1919; Office of the Custodian of Enemy Property, Bangkok, to C. de Holck)

In this letter, the Custodian of Enemy Properties’ denial of Gyldenstolpe’s requests is followed by the Custodian proposing a valuation from Mr. W.J.F. Williamson, a British Zoologist and Ornithologist who also serves as President of the Natural History Society of Siam. The letter ends with the custodian saying they may provide the collection to the Museum based on Williamson’s final estimate.

Jumbled collection contents

Accepting that they could not check the collection and probably based on Mr W.J.F. Williamson’s appraisal, the next letter in the collection, dated 13 September 1919, states that the Museum accepted a price of 1514.25 Ticals for the entire collection.

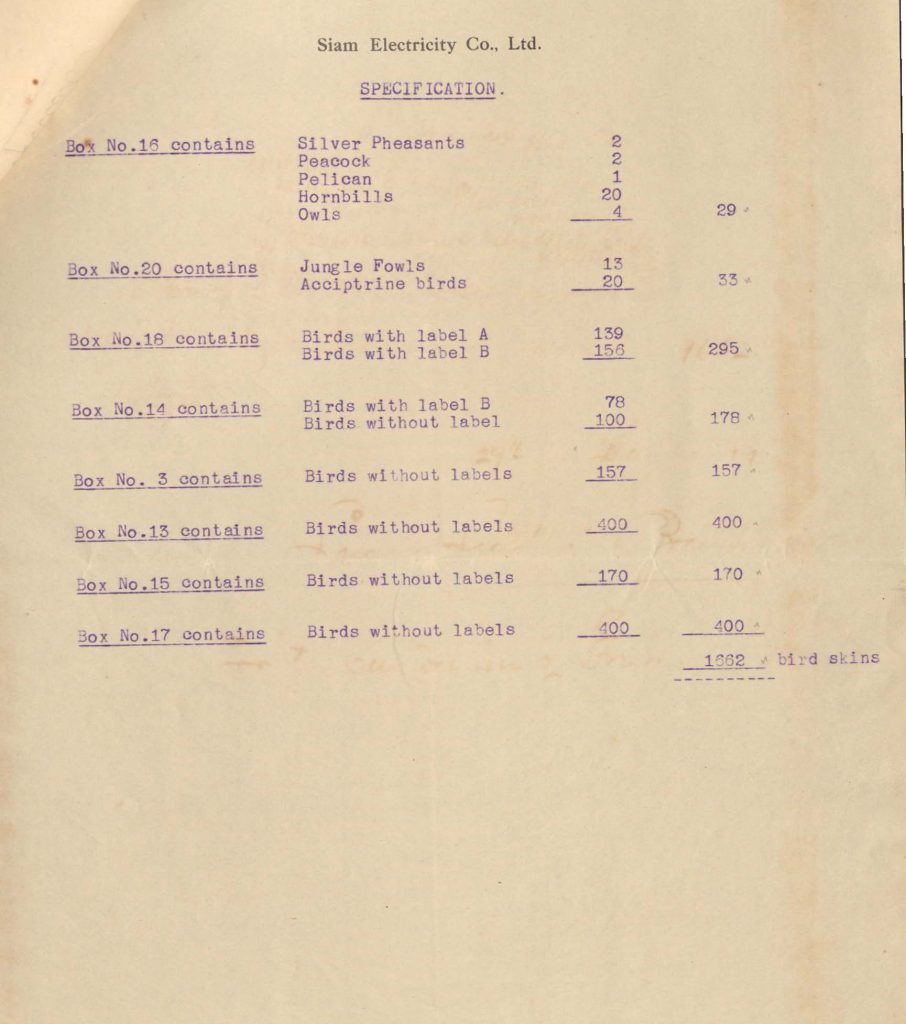

The Danish-run company Siam Electricity Company Ltd. pays this cost on behalf of the Swedish embassy, which in turn acts on behalf of the Museum in Stockholm. As it was made clear that the zoological objects of Eisenhofer’s collection had been mixed up with the contents of another owned by a Mr. Hetzka, a new challenge arose. The Siam Electricity Co. Ltd. had to figure out which ones of the zoological objects did not belong in Eisenhofer’s collection, and according to a letter from the company representatives dated the second of January 1920, it appears that the collections were unsorted, likely causing more issues.

“As mentioned by our Mr. Bisgaard-Thomsen the Custodian office had 55 birdskins left over, due to the fact that Mr. Hertzka’s collection in some way or other was mixed with that of Mr. Eisenhofer. According to your [von Holcks’] instruction we refused to pay for and to take delivery of these skins, which were picked out from the unassorted lot without labels.” (2 January 1920. H. Elsøe, assistant manager at the Siam Electricity Co. in Bangkok, to the Royal Swedish Consulate General)

The issues of payment

After retaining the collection, the Siam Electricity Co. paid, expecting the Museum to reimburse them. Representatives H. Elsøe and W. L. Grut addressed letters to the chargé d’affaires von Holck, who acted as a middleman, in February 1920 stating their costs were 1523.85 Ticals. This included the charge paid to the Custodian of Enemy Property for the collection and the business that packaged the items. Von Holck was instructed to provide an invoice to Einar Lönnberg, the intendant of the Swedish Museum of Natural History’s vertebrate division where Gyldenstolpe worked, for the funds owed. The company required to be reimbursed at the earliest convenience. However, as will be made clear, the Museum experienced payment issues for one reason or another, seemingly prompting the Siam Electricity Co. to assume more financial responsibility than they should have and the chargé d’affaires having to send multiple information letters to the Museum and its staff.

A letter from 12 February 1920 outlines some of the concerns, indicating the Museum made a payment. However, it did not repay the whole amount and paid to the chargé d’affaires instead of the Siam Electricity Co. as required. Hence, the firm had to ask von Holck to transfer the funds and then write again to Lönnberg, demanding he send the remaining balance straight to the Siam electrical company’s headquarters in Copenhagen.

Shipment

In another letter from 12 February 1920, the chargé d’affaires mentions to the representatives of Siam Electricity Co. that the freight will be handled by the East Asiatic Company’s ship M/S “Selandia” for an unknown fee. Following this, the Siam electricity firm presented the Consulate with the East Asiatic Co’s bill for the transport of products on the 24th of February 1920, totaling 212.00 ticals. In the letter, they state that the Consulate is responsible for the payment and that they were only sending this bill forward. Furthermore, they notified the chargé d’affaires that the shipment had only reached Copenhagen and asked to let Lönnberg know he had to fix transport to Stockholm.

In a response dated 26 February 1920, von Holck specifically thanked the Managing director Mr. W.L. Grut at Siam Electricity Co. for taking on the inconvenience of expanding the affair so far and all the work that went into acquiring and sending the wares. However, he still requested a favor as the Consulate did not possess any funds;

“I am asking you to also be so kind as to pay Ø.K.’s freight bill here, as the Swedish Consulate General is not in possession of funds, and it will be most fortunate to combine all disbursements on one hand (…). Besides, I will soon take leave, and the consulate will pass into your hands.” (26 February 1920. C. de Holck, acting general consul for Sweden, to Commander W.L. Grut)

In addition, Lönnberg wrote to von Holck. He appears to have deposited into the chargé d’affaires’ account once more. He also advises that the Consulate arranged for the collection’s move from Copenhagen to Stockholm through the Danish East Asiatic Company, which had previously assisted the National Museum. The last letters in the collection only imply that the Consulate handled the transportation, as they mostly deal with payment issues, with the chargé d’affaires transferring the money that was incorrectly sent to him to the Siam Electricity Co., and the said company once again requesting von Holck to ask Lönnberg and the Museum for their remaining balance.

Epilogue

While writing this blog article, I, the author of this post, was interested in what happened to the zoological artifacts after the last letters in the collection. With the idea that the collection did make it to the Museum, I thought of looking to them for information. Though there was very little specific information available, the Swedish Museum of Natural History’s website provided some indicators.

Regarding the bird skins, Count Nils Gyldenstolpe, one of the actors in our letter collection, is said to have supervised the last thorough review of bird-type specimens in 1926. The Swedish Museum of Natural History is then noted to have featured 283 bird types, and there is no record of that inventory decreasing over time. What is more crucial for the question of whether the bird skins remain in the Museum is the statement that their skin collection comprises about 65% of the world’s bird species. Without knowing all about birds, one may assume that this proportion includes some Siam-native species.

There wasn’t much information about the Siamese deer and bison horns either. However, the Museum claims pieces of their mammal inventory date back to at least the 18th century, which indicates older material is not discarded. Something that suggests the Museum might still have the pieces imported from Eisenhofers collection is that a significant portion of their mammal inventory is from Southeast Asia, which includes Siam or modern-day Thailand.

As far as I can determine, Emil Eisenhofer’s zoological objects might still be in the Museum’s inventory and on display today.

_______

Author: Klara Nielsen Styrman, research assistant 2024.

Editor: Karin Zackari, researcher.

References

“Count Nils Gyldenstolpe’s negotiations regarding E. Eisenhofer’s collection of bird skins”, Correspondence, Royal Swedish Consulate General. SE/RA/231/231009.1, E 1:7.

Gyldenstolpe, Nils. B.A., “List of Birds Collected by Mr. Emil Eisenhofer in Northern Siam”,

The Journal of the Natural History Society of Siam, Vol.1, no. 3. 1915. pp. 163–172.

Gyldenstolpe, Nils. D. Sc. “A List of the Mammals at Present Known to Inhabit Siam”, The Journal of the Natural History Society of Siam. vol. 3, no. 3, 1918, pp. 127–175.

Gyldenstolpe, Nils. Zoological results of the Swedish Zoological expeditions to Siam 1911-1912 & 1914-1915 5 Mammals 2, Stockholm, 1916.

Comments